Green and Inclusive Public Procurement Driving Change – Advocating the case of social housing in India

The pursuit of human prosperity for all within planetary boundaries, as committed by governments as part of the Global Agenda 2030, requires that national policy strategies address sustainability in consumption and production of goods and services in all economic sectors.

This has appropriately put the lens on ‘public procurement’ as a mechanism to transition towards green and inclusive economies. The public sector represented by the government and its agencies at different levels of governance is not just a big consumer of goods and services, it also directs and drives consumption in the private sector. Influencing shifts in consumption behaviours, whether public or private (state or the market), is expected to drive shifts in production systems (and vice versa). This is the basic premise of bundling Sustainable Consumption (SC) and Sustainable Production (SP) together.

The case of the building and construction sector in India is interesting to study in this perspective. This sector has an immense impact on the environment being the largest consumer of non-renewable minerals, the extraction of which has multitude cross sectoral impacts on food, water and energy systems. It is also among the largest emitters of Green House Gases, contributing to and therefore with a potential for mitigating global warming.

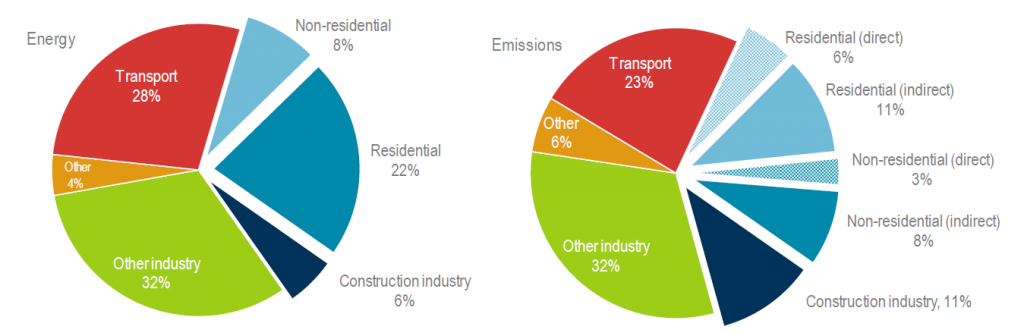

Figure 1: Global share of building and construction in energy and emissions, 2017 Source: IEA & UNEP (2018)

The sub-sectors of housing and infrastructure form the bulk of the construction sector. It is interesting that while consumption in infrastructure is public sector driven, in housing, it is primarily driven by individuals and private developers. The bulk of the building products and production systems for both sub-sectors are the same – cement, bricks, steel, glass and aggregates, water and timber.

Housing, especially social housing, is not only the largest component of the housing subsector, it is very interesting from the point of view of Green and Inclusive Public Procurement driving a change. And even though consumers of social housing are private individuals and families; there is a tremendous potential for influencing this consumption by the public sector, through the affordable credit support, state subsidy and the regulatory eco-system of approvals and certification in the delivery of social housing. In addition, although a large percentage of housing is constructed through the private market route – by individual families in villages and small towns, and small developers or housing companies in towns and cities; public sector construction activity and the regulatory environment around housing has a huge influence on how the private sector builds houses, including the material and technology choices it makes.

Influencing the housing market towards green consumption, through public procurement, would have a huge impression on the ecological impact of the housing sector and on the distribution of economic benefits from this sector.

Figure 4: Green Public procurement resulted in construction of low-cost, eco-friendly building under the DST-TIME LEARN project in Uttarakhand

Social housing in India addresses the shelter needs of the economically weaker sections of the society in rural and urban regions, through grant support and affordable credit mechanisms. Social housing is also supported through providing or making land available for families below poverty line in rural areas and slum dwellers in urban areas.

In both urban and rural social housing, the primary emphasis is on financial subsidies. Decision making regarding what may be constructed rests either directly with the beneficiary or through a developer route for the beneficiary. Housing is also ‘provided’ by public agencies, in which case the decision making regarding the technology and materials for construction rests with the concerned public agency (usually the municipality or a housing board). Housing developments in this case are delivered by construction companies who bid for the same through public tenders.

Figure 5: Green public procurement of alternate building material such as fly ash bricks for construction of dwelling units for EWS under VAMBAY scheme in Vijayawada. Source: MOHUA

In order to meet time and scale targets along with technical and quality compliance, the government at the Centre and the States have set in place an institutional ecosystem that is expected to promote social housing schemes, reach out to beneficiaries, train artisans, facilitate credit support, provide technical designs, supervise construction (where required) and provide approvals. For both urban and rural areas, governments have also recognised the need to promote sustainability in social housing. Sustainable housing has broadly been understood as housing that reduces negative impact on the environment, and many terminologies ranging from local materials, green material use, energy efficient housing, green construction etc. are used in policy and programme documents and communication at different fora on sustainable housing.

The intent is clear – there is a recognition that the pace and scale of housing required and being constructed in India has a negative impact on the natural ecosystem, and that the material energy demands of this sub-sector are making housing unaffordable to the poorest. The issues that most concern us, therefore, with respect to social housing are:

- Minimising the non-renewable virgin material footprint of housing – soil, sand, stone (including limestone for cement), aggregates, metals

- Ensuring sustainability of the renewable material used in housing – timber, water

- Minimising building energy requirement – embodied fossil energy in materials and fossil energy for operation and use of buildings

- Closing the material-energy loops though post life management of the building

- Maximising the job creation potential of housing production, and the local economy benefits from the production and servicing of housing.

Greening the public procurement of building materials can have a profound impact on the aim to minimise the ecological footprint of the housing sub-sector.

Social housing construction procurement currently prioritises lowest cost, fastest time and structural performance. Ecological parameters such as the ones listed above are normally not specified in public tenders for housing construction. Contractors and developers who bid for social and affordable housing projects address the needs of cost and speed, and procure construction materials such as bricks, cement, steel reinforcement bars and sections and building products such as roof and wall pre-fabricated elements, door and window frames, paints, etc. on the basis of (a) cheapest price point, and (b) conforming to BIS codes (for structural and quality standards). Private individuals who purchase material for home construction do so on the basis of price and quality aspirations influenced by peers, neighbours and government construction.

Ecological parameters as mentioned above are desirable, but not mandated, and therefore rarely included in decision making by public agencies. The advocacy for ‘green (and inclusive) procurement of social housing’ has faced arguments such as – “housing is a private activity (even if supported by public agencies) and choices can be influenced, not mandated”, “we can use green products as long as these are not more expensive (actually cheaper) than conventional (read environmentally harmful) construction practices” and, “there are not enough suppliers for green material and construction agencies equipped to deliver green construction”.

Consumption drives supply, and thus, green and inclusive public procurement of housing can influence shifts in the upstream processes of building technology choice and construction practices, and consequently in the systems of production of building materials; thus moving this whole sector towards sustainability.

Greening the procurement of the housing sub-sector through a focus on building materials would require:

- Methodologies and tools to assess ecological footprints, job creation and lifecycle costs

- Eco-labeling of products such as bricks, cement, paints, concretes and pre-fabricated products

- Standards and benchmarks for labeling

- Public disclosures by material producers and developers

- Lifecycle assessment of resource and energy footprints

- Verification and certification of the footprints and disclosures, and an institutional framework for the same

- Regulations that define maximum footprints allowable in procurement

- Incentives for industry – material producers and housing developers; and for consumers – public agencies and private home owners

- Investments from development banks in the sector linked to green procurement policies

- Capacity development of the institutional system, the market players and consumers, with respect to green production and consumption of housing and building material.

Fortunately, a lot of work has already been done in this sector by way of methodological and assessment studies on material and energy footprints, verification and certification mechanisms such as GRIHA, IGBC etc., technical viability through demonstration and testing and design of production systems at both the industrial and MSME scale providing a range of business models for green building materials. This provides us a running start in this sector.

So what holds green public procurement of housing and building material back? The key barriers are:

1. Incoherence in policy formulation. Public policy in India rarely takes a systems view in its design and implementation. There is a bureaucratic separation between environmental concerns of resource stress, development concerns of housing delivery, and economic potential of the housing market. A similar disconnect can be seen between the production of housing and the production of material for housing.

On the one hand, the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs and the Ministry of Rural Development are devising strategies for ensuring that around 40 million families are able to access social and affordable housing by 2022; on the other, there is inadequate attention to the environmental impact of this immense production of housing in such a small time scale. The intent for ‘sustainability’ in social and affordable housing is not backed up by credible data on the negative environmental impacts and potential job creation benefits of technologies being promoted for housing. Similarly, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change is concerned about natural resource stress and pollution caused by various industrial processes, including housing construction, but is yet to find a way to translate this concern into active guidelines for the construction sector. The Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises and the Ministry of Industries and Commerce, who have a stake and a mandate to promote industrial development including manufacturing of building products, have also not established material, water and fossil energy guidelines and standards for the sector. The Ministry of Mines, the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare, and the Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship are all stakeholders in the upstream processes of housing delivery, but are not adequately engaged from the point of view of establishing guidelines, regulations, standards or capacities that need to be enhanced.

2. Investments that promote green and sustainable housing have had a limited view sustainability. National and international development finance invested in the housing market, has primarily addressed ‘sustainability’ through a building energy efficiency route. In implementation and certification, this has merely focused on operational energy efficiency of buildings and appliances. Therefore, embodied energy and resource criticality criteria have never been applied, and job creation potential has not even been addressed in investments. This has separated the processes of housing construction from the processes of material production for housing, limiting the gains and therefore the potential of public procurement to influence the greening of this sector.

3. No mandatory environmental quality standards for building material. Standards for resource and energy footprints of products — an essential step in Green and Inclusive Public Procurement — need to be based not only on resource stress for the specific sector, but also have to take into account the potential conflicts across different economic sectors and the maintenance of ecosystem services.

Figure 6: Parameters of criticality of resources to be considered as a basis for Green and Inclusive Public Procurement Source: MaS-SHIP 3rd Stakeholder Dialogue (2017)

The mandatory BIS codes for building materials for construction of buildings and housing, provide a minimum structural quality performance along with testing and certification methods for raw materials and building products. Environmental quality performance of any building material and product should also be made mandatory. A maximum allowable percentage of non-renewable (virgin) raw material, source of (sustainably managed) renewable raw material and fossil based embodied energy should be prescribed for a building product or element. This prescription should be followed up in the specifications for design and construction of housing in the tender documents. We could start with the materials that are bulk, have the highest ecological impact, and for which production information is available, such as masonry bricks, cement, concretes and steel.

4. Inadequate data on material and energy flows in the housing sector and available secondary resources. Greening public procurement of housing in India will require knowledge of the scale of virgin mineral resources and fossil energy being consumed, and the purpose for this use, along with possible secondary resources that may replace virgin resources. This requires mandatory formal disclosures by producers and consumers (building designers and contractors) of actual raw material and energy consumed in material production and construction, and a dynamic database of secondary materials and sustainably managed renewable materials distributed across the country. These would be by-products from iron and steel manufacturing, power sector, construction debris, bamboo, secondary timber, old building salvage etc. There is a lack of complete and credible information about resources and embodied energy in building materials and products. In the absence of such information, incentives and regulations for promoting resource efficiency and circularity through public procurement are not possible. Currently, some designers and building developers do disclose the carbon and material footprints of their buildings, and the nascent, but growing, certification system (GRIHA) does promote such buildings. However, this is voluntary, and not mandatory; it does not result in any incentives for the consumer, and is dependent on whatever information producers of building materials are willing to disclose, which in many cases is not forthcoming.

5. Support to supply chains of ‘green building material producers’ is not forthcoming. Poor availability leads to increased costs, and price point is a significant factor in actual procurement. This is a chicken and egg problem. Public procurement can provide a guaranteed market to suppliers of green building materials. However, experience indicates that it is not so simple. The business of ‘brown’ is well entrenched in the market, and also in the consumption decisions of public procurement cells. Supply end interventions can help break the dead-lock. Techno-financial interventions, targeted at material production businesses, such as credit support at affordable rates, incentives or tax holidays to ‘green’ businesses, environmental taxes on the ‘brown’, and technical services to maintain product quality, can enable a level playing field to nascent green businesses in the building material production space.

In conclusion, green and inclusive public procurement strategies can have a significant impact on reducing resource stress and mitigating GHG emissions, if applied on the fast growing housing sector. Social housing is an important intervention area from the point of view of public procurement driving a change, as it is the largest component of the housing sub-sector. It is also a sector in which private consumption is supported by public finance. The points of intervention in the construction of houses and in the procurement of building material mean that upstream supply chains are influenced. Public procurement, thus, has a sector wide impact, driving change in the private market of housing and building construction.

Zeenat Niazi

Development Alternatives

zniazi@devalt.org

The views expressed in the article are those of the author’s and not necessarily those of Development Alternatives.

________________________________________

References

Caleb, P. R., Gokarakonda, S., Jain, R., Niazi, Z., Rathi, V., Shrestha, S., . . . Topp, K. (2017). Decoupling Energy and Resource use from Growth in Indian Construction Sector. New Delhi: GIZ. Nagrath, K., Reen, R., & Niazi, Z. (2016). Achievinmg resource synergies for a rapidly urbanizing India. New Delhi: Development Alternatives, Heinrich Böll Foundation. Satpathy, I., Malik, J. K., Arora, N., Kapur, S., Saluja, S., Shekhar, A. R., and Dandapani, V. (2016). Material Consumption Patterns in India. New Delhi: GIZ. Shekhar, A. R., Dandapani, V., Nagrath, K., Rathi, V., Banarjee, A., Saluja, . . . Becker, U. (2015). Resource Efficiency in the Indian Construction Sector. New Delhi: GIZ.

Leave a Reply