GREEN BONDING! OUR WAY TO SUSTAINABLE ENERGY?

Amongst all the sectors in modern India, the energy sector is in vogue. And, why not? The fourth largest energy consumer in the world, India, already imports a substantial portion of its energy. As India continues to grow, a key concern for sustaining its growth will be to meet its energy demands. It is already set to overtake China in the next decade, as the primary driver of energy demand.[i] Given the state of its domestic market, rapid urbanisation, burgeoning population, and growing challenges of climate change (India is third after US and China in green house gas emissions) “energy security concerns will only further intensify”.[ii]

With the long growing question marks on reliance on fossil fuel and old energy systems, it appears fundamental changes are underway in India’s energy sector. Centered primarily on renewable energy, India is trying to free itself of a high carbon development and create a greener economy.[1] Regarded as the third most attractive market for renewable energy, India has set itself an ambitious target of achieving 55 GW by 2019 and 175 GW of renewable energy capacity by 2022, from a current figure of 30 GW.

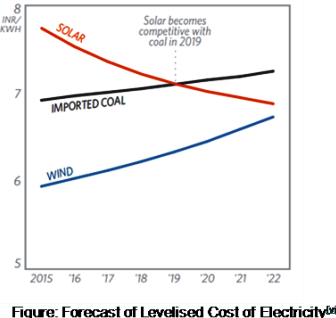

This rapid transformation towards renewable energy is not entirely guided by altruistic motivations. Besides the obvious environmental benefits, there is a growing realisation of multiple economic and social benefits of clean energy. Many of the renewable sources, especially solar and wind energy are now within reach of achieving grid parity – they are becoming cost-competitive. Not just relying on subsidies, these renewables will “cost the same as power produced from traditional sources and available on the nation’s transmission and distribution grid”.[iii]

The cost of wind power is already competitive and solar power will achieve grid parity by 2019.[iv] Furthermore, India is amongst the top 10 countries with largest renewable energy employment, with a potential of creating more than 1 million jobs by 2022.[v] Such a transition, however, demands an impressive US $200 billion in funding. High rates of interest and poor terms for debt raise the cost of clean energy in India by 24 to 32 per cent, as compared to US and Europe.[vii] This together with insufficient budgetary allocation and a large fiscal deficit makes financing a daunting task.

Enter ‘green’ bonds

Like any other bond, it is a financial instrument used for raising funds from the debt market.  The difference arises with the label ‘green’ – funds may only be used for those projects relating to renewable energy, climate-mitigation/adaptation etc. By utilising the already set processes, green bonds are an elegant system for stimulating finance for clean and green development.

The difference arises with the label ‘green’ – funds may only be used for those projects relating to renewable energy, climate-mitigation/adaptation etc. By utilising the already set processes, green bonds are an elegant system for stimulating finance for clean and green development.

The lower rates of interest on such bonds make it attractive for the issuer, besides the consequent improvement in their goodwill in the market.[2] For the investor, the incentive lies in a stable return, as the risk of non-performance lies with the issuer.[3]

As a result, appetite for green bonds has surged, as shown by a rapidly growing market. Globally, it has increased by 3-folds in size to US $37 billion in 2014 (year-on-year) and is forecasted to jump to US $100 billion mark by the end of 2015.[viii] Historically, led by multilateral banks such as World Bank, Asian Development Bank, European Investment Bank and national governments, many corporate players are now entering the field. In India, the Export-Import Bank kick-started green bonds, issuing bonds worth US $500 million, followed by Yes Bank, which has raised US $160 million.[ix] The oversubscription in these issues highlights the keenness amongst investors to take on projects with high positive environmental impact.

The question is can ‘green’ bonds be the magical solution?

The answer, unfortunately, is a bit murky. While ‘green’ bonds seem to offer us a good alternative, the market is still at its infancy to be certain. The definition and standards of a ‘green’ bond are rather vague, as it has mostly been left at the discretion of the issuer. The danger of ‘greenwashing’[4] along with the ambiguity on transparency and reporting aspects increases the risk of dampening investors’ confidence and the market’s integrity. For example, GDF Suez, which issued US $3.4 million green bonds in 2014, but was later accused by NGO International Rivers of building a dam in Amazon with disastrous ecological implications.[x] For most skeptics the label green is “merely a slang designation”, heightened by the lack of agreement in the science community on how to conduct a cost-benefit analysis with respect to climate change and other environmental impacts.[xi] For instance, are bonds issued by a nuclear power plant to be considered green, as on one hand there is lowering of emissions, but on the other creation of toxic waste?[xii]

The problem becomes murkier, with the issue of ‘additionality’ – are green bonds enabling funding of new projects (new capital) or simply refinancing old ones producing no ‘new’ environmental benefits. For example, the repackaging of its existing loans and selling them as ‘social impact bonds’ by Lloyds Bank [xiii] or refinancing of bonds that were initially issued for building energy efficient building by MIT.[xiv] Such uncertainty could potentially curtail market growth. India, further, faces the challenges of high currency hedging costs, poor sovereign ratings (currently at BBB-), double taxation, and low tenure (averaging 3-10 years as compared to 10-15 years in other countries).[xv]

The problem becomes murkier, with the issue of ‘additionality’ – are green bonds enabling funding of new projects (new capital) or simply refinancing old ones producing no ‘new’ environmental benefits. For example, the repackaging of its existing loans and selling them as ‘social impact bonds’ by Lloyds Bank [xiii] or refinancing of bonds that were initially issued for building energy efficient building by MIT.[xiv] Such uncertainty could potentially curtail market growth. India, further, faces the challenges of high currency hedging costs, poor sovereign ratings (currently at BBB-), double taxation, and low tenure (averaging 3-10 years as compared to 10-15 years in other countries).[xv]

Efforts are being made in the forms of Green Bond Principles (voluntary guidelines for issuance of green bonds), standards and list of third party verifiers by Climate Bond Initiative, the Principles for Responsible Investment, and Centre for International Climate and Environmental Research (CICERO) Second Opinion, etc. These are, however, voluntary guidelines and still in the development stage.

For a healthy development of the green bond market, there must a clearer and more consistent understanding of definitions and standards including impact assessments, reporting etc. The market does not demand a rigid stance. As the Economist rightly notes “it needs to strike a balance between accepting anything (diluting the attraction of green bonds as instruments to diversify climate risk) and being so strict that hardly anyone can meet the criteria.”[xvi] In India, PACE-D have further recommended: (1) enhancing the risk liquidity facility to counter higher costs due to currency fluctuations (2) seeking support from the Green Climate Fund for risk mitigation products (3) reducing hedging costs via indexing electricity tariffs to inflation etc.[xvii] Given the trends, it seems that green bonds are to stay. The direction in which they will finally head, it is too early to comment. q

Mandira Thakur

mandirathakur@gmail.com

Leave a Reply